And other musings on adaptation in the wake of Denis Villeneuve’s Dune and the recently announced film versions of L’Incal and Hyperion.

Frank Herbert’s Dune sci-fi novels have had a rough history when it comes to adaptations for the big screen. Surreal fantasist Alejandro Jodorowsky (still going at the age of 92, bless him) famously tried to make a Dune movie in the 1970s, but his attempt failed – well, it’s difficult to say that it failed, because while it wasn’t produced, its ideas, concept art, and highly talented creative staff (including Moebius, H.R. Giger, and Dan O’Bannon) would go on to transmit the project’s DNA into Alien, Star Wars and Blade Runner. David Lynch made a maligned version of Dune in 1984; it was confusing, difficult, and just couldn’t get the story or universe right.

Adapting a book into a movie is a weird thing. Dune was considered un-adaptable for many years, with Jodorowsky’s incomplete production and Lynch’s misfire taken as evidence that Herbert’s world just couldn’t be translated to film. But now we have a big Dune movie from director Denis Villeneuve, and guess what? It’s pretty good, and it’s very faithful to the book. There are a few issues that amount to questions of interpretation – the film feels more grim than the novel, there are places where exposition needed to be clearer, and I think that the film loses out on a bit of emotional texture by cutting out early scenes where the characters just talk to each other – but we can very much say that Herbert’s Dune has been intelligently and compellingly adapted into a movie. Dune wasn’t impossible to adapt after all.

The truth is that Dune was never impossible to adapt. It was just a large sci-fi book that called for a lot of unusual terms that needed elaborate explanations (kwisatz haderach, etc.) and a huge budget to pull off the sandworms and starships. The real problems were how to make it palatable and interesting to mainstream audiences, and how to do justice to the story in a single film. Villeneuve wound up solving both of these problems in an unexpected way: first, gamble on the fact that a significant portion of the audience would be willing to come along for the ride without being catered to and without needing to have everything simplified (the popularity of complicated fantasy universes like Game of Thrones might have been a proof of concept here; it’s no surprise that Game of Thrones‘ Jason Momoa also features in Dune), and second, simply split the story into two movies without worrying about fitting it all into one.

The Limits of Adaptation

This discussion about Dune‘s adaptability got me thinking about texts that are impossible to adapt and why it doesn’t make sense to even try. Take, for instance, the 1962 novel Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov. The book is, on the surface, simply a long, autobiographical work by a modernist poet named John Shade. But the real story is in the poem’s annotations, written by an editor who might be a scholar or a madman or the exiled king of a fictional nation.

How would you go about making a film adaptation of Pale Fire? The whole point of the book and the experience of reading it is that you negotiate back and forth between the poem and the notes, teasing out the ways they relate to each other and parsing the cryptic mystery of what is really going on in the editor’s head. There might be a few ways to approximate it in a movie: one could film a kind of autobiographical tone poem of a film in the style of, say, Stan Brakhage or Maya Deren, and then include an audio commentary by a critic or scholar, which would make up the true meat of the film. But if Pale Fire were adapted in this way, we’d lose out on the tangible and very precise sensation of flipping back and forth through the book’s pages on a scavenger hunt, finding clues, comparing phrases, moving through it in a process that is scripted by Nabokov but that allows for jazz-like spontaneity and reader agency.

Even if we are able to figure out one way or another to fake it, should we bother? Taking Pale Fire out of its context would mean excising the purpose that makes it compelling, and I’d say that any attempt to replace that purpose would be inadequate, if well-meaning. This is one of the limits of adaptation: if a text is purposefully shaped by its medium to the extent that it is, in a way, about that medium, about the way that we read or listen to or interact with it, then it can’t be removed from its medium and implanted elsewhere without killing it off.

Pale Fire without its current formal structure is meaningless, and we could say the same thing about turning a number of other novels into movies. How do you adapt Julio Cortázar’s novel Hopscotch, which has a jumbled-up chapter structure that can be read in a linear order, in an order recommended by the author, or in whatever order you choose at a given moment? Or could anyone make a film of James Joyce’s Ulysses without losing its central conceit, which is to preserve the mood and feel and psychic architecture of Dublin in the early 20th century? I don’t think a CGI version of turn-of-the-century Dublin would have quite the same effect.

Now, doing a project that is spiritually inspired by something like Pale Fire or Hopscotch could be fantastic, and a contemporary filmmaker with his or her own cinematic take on preserving the texture of modern day Dublin, Joyce-style, would be great. But to do a straight adaptation of these books wouldn’t make much creative sense.

Of course, no one out there is wasting their time making a Pale Fire movie. So why am I going on about this?

The New Wave of Adaptations

We usually take it for granted that self-consciously literary works like Pale Fire aren’t going to be made into movies and that doing so would miss the point. However, we rarely extend this courtesy to science-fiction and fantasy novels; many readers seem to feel that just because a book features spaceships and aliens, it would make a great movie. But there quite a few sci-fi and fantasy books that are just as inextricably bound to their medium and formal context as Pale Fire and other pieces of high literature.

It’s worth considering how and why these sci-fi and fantasy works are un-adaptable, because some studio will certainly try to adapt them, sooner or later. The success of Game of Thrones means that every genre book in literary history is being eyed for potential adaptation. We’ve had or will soon have movies or shows based on The Expanse, The Wheel of Time, The Witcher, a new Lord of the Rings series, Asimov’s Foundation books (themselves considered impossible to adapt, a problem that the producers have solved by inventing a new story and characters), and yes, Dune, among others. There aren’t too many other big books left to draw from.

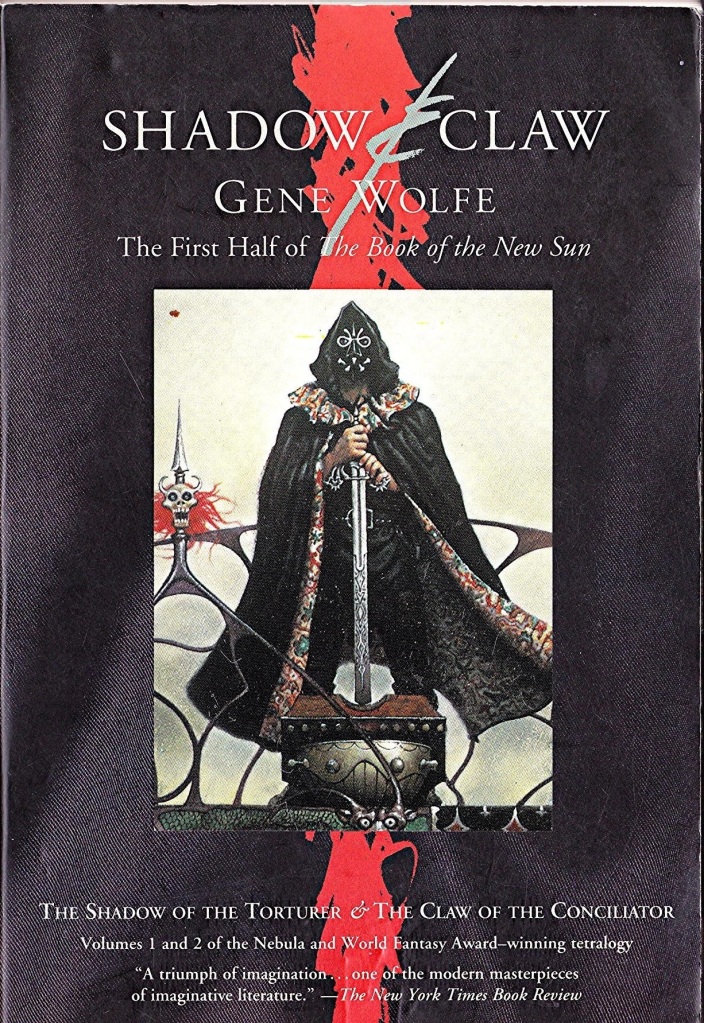

This means that studios will turn their attention to what remains: material like Hyperion and Book of the New Sun and a number of other book series with cult followings and the potential for CGI spectacles like alien monsters and space battles. But there’s a good reason that these books haven’t been adapted – and it’s not just a question of budget.

Dan Simmons’ Hyperion, for instance, is a space opera about time travel, artificial intelligence, colonization, and a strange, deadly creature called the Shrike. Its most important character is a cybernetic clone of nineteenth century Romantic poet John Keats. Yes, you read that right. I won’t give too much away here, but Cyber-Keats is central to the story, and he becomes even more important in Hyperion‘s direct sequel, Fall of Hyperion.

Everything that we know about John Keats, aside from a few portraits, is on the printed page. He was a great poet and he wrote intelligently about literature and his own reflections on life in his correspondence with his brothers and literary friends. If we read about cybernetic and cloned versions of John Keats in a book, this tracks with how we’ve experienced Keats before: in the pages of a book. When Simmons seeds Hyperion with lines from Keats’ poems (and the novel is filled with allusions to Keats; even its title is taken from one of Keats’ epic works), this doesn’t feel incongruous, because Keats and his legacy are all based in writing and books.

A movie rendition of Keats, however, has no history or legacy to draw from. How are movies in any way related to Keats? They aren’t. What relationship does Keats have with movies? No relationship at all (unless you count the sentimental Keats biopic Bright Star from 2009). If an android John Keats shows up in a movie, there just isn’t the same effect that you get from an android Keats appearing in a book.

Whatever philosophical reservations I may have about the value of a Hyperion movie, we’re in for one anyway: Bradley Cooper’s production company recently declared its intention to turn Hyperion into a big film, presumably inspired in part by Dune‘s success.

I have the same reservations about adapting Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun series, which may be the most self-consciously literary work of science-fiction or fantasy I’ve ever read. It is a sprawling, epic memoir of Severian, a torturer’s apprentice who lives in the far-flung future. His world is slowly dying, but in a roundabout way, he may have the chance to do something about it; the path to renewal will take him on a painful but profound journey of self-discovery involving reincarnation, mystical powers, and alien gods.

The New Sun novels are fascinating books, in part because Wolfe fills them with unusual and mysterious words that seem to have been forged in the strange atmosphere of the future; a few of the series’ memorable words are destrier for horse, carnifex for executioner, fuligin for dark black. But these words aren’t invented like Tolkien’s Elvish or the magical terms of Harry Potter and other fantasy novels. Instead, Wolfe plucked them from dead languages like Latin, choosing words that are sufficiently obscure so that we won’t easily recognize them but that we may be familiar with in some dim sense, because old languages left their mark on newer languages in so many ways.

If this leads to a false recognition here or there – a reader might think the name of the Ascian people in the books is a reference to “Asians”, but it is actually taken from ἄσκιος, the ancient Greek word for “without shadow” – this is part of the literary game that Wolfe wants to play with us.

Wolfe contextualizes his word choices by framing Book of the New Sun in a truly unusual and unique way: he says that he is translating a piece of literature from the future, working from a text in a futuristic language that he can only barely render into English. Wolfe claims to be immersed in “the study of the posthistoric world” and he has challenged himself to translate Severian’s story to us, the people of the past, as closely as possible. How Wolfe got his hands on a book from the future is left amusingly undeclared. Because he is translating a text from the future in a future language, Wolfe must take exceptional steps to capture the meaning of these future words as closely as he can, and this is why he uses dead languages: sometimes, dead languages can say and express things that modern words can’t.

It’s clear that Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun is a deeply literary creation, interested in language, writing, and reading. If these books were adapted into a movie, they wouldn’t have the same meaning. The process of reading Wolfe’s books and the surprise we feel when we encounter their words is integral to their purpose.

It’s true that it doesn’t seem like any studio wants to make a Book of the New Sun movie – well, there aren’t any announced plans, at least, and there could very well be some treatment out there in development hell – but it’s a much-requested adaptation by fans, and I think that, at some point, someone will get the idea to give it a go. Let’s make a bet that it’ll happen in the next six years.

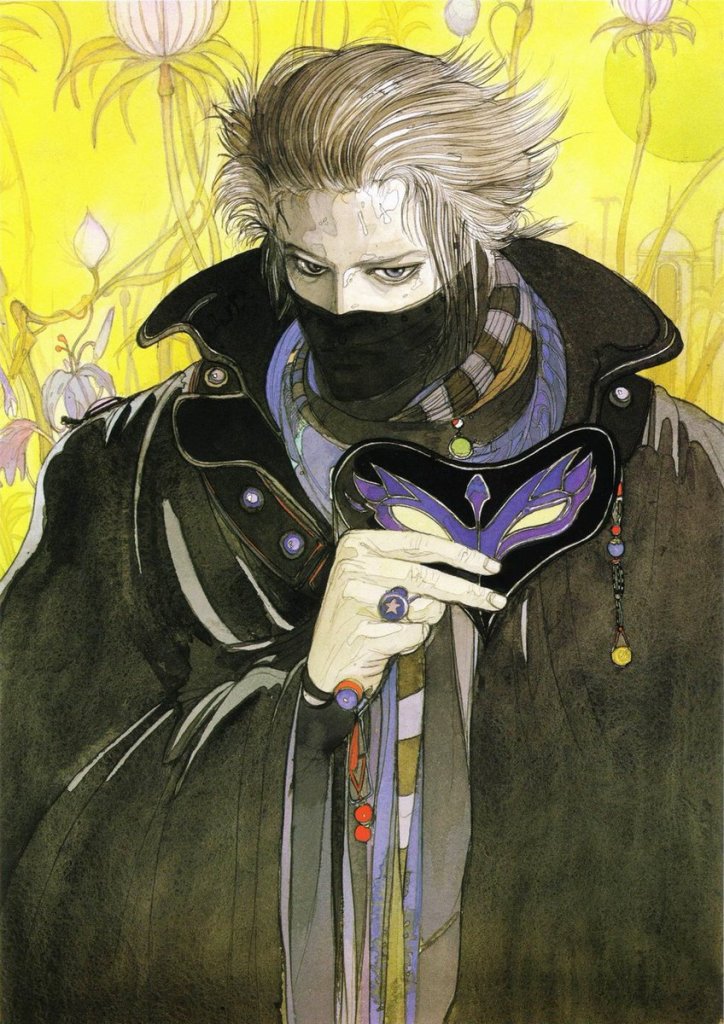

After big studios have grown tired of mining classic sci-fi and fantasy literature for adaptation fodder, they’ll turn to other sources for otherworldly material, like Japanese anime (Cowboy Bebop and eventually we’ll get One Piece), video games (Uncharted), and an effort to make a lot of old comic books (L’Incal, the graphic novel sci-fi saga created by Alejandro Jodorowsky and Moebius after their Dune movie fell apart, is up for an adaptation by Taika Waititi…but if L’Incal really needs an adaptation is another story).

I‘m positive that this environment, in which studios are so hungrily hunting for something to produce (preferably material with some level of name recognition and the potential for viral appeal) someone in Hollywood will try to make a Watchmen movie again.

Watchmen‘s Formal Specificity

That brings me to the point of this article.

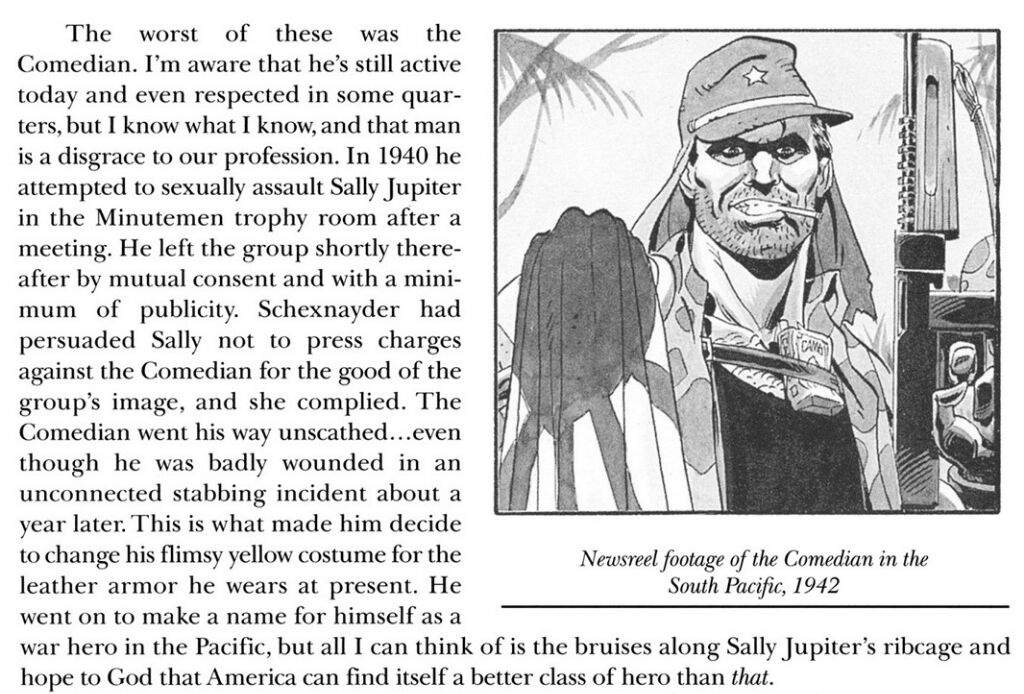

The first movie adaptation of Watchmen wasn’t good – more on that later – but trying again is just too tempting to resist. For the uninitiated, Watchmen is a seminal graphic novel from the 1980s, written by Alan Moore, who is likely the most acclaimed name in modern comics, and drawn by Dave Gibbons. The graphic novel is about a lot of things, but it’s mostly about what would happen if superheroes really existed. Wouldn’t they be deranged? Consumed by their own incredible powers? Could we really expect that superheroes with godly abilities like, say, Superman, would care about human beings and their petty issues?

Watchmen follows a group of superhero characters who confront their own answers to these questions. Some of them manage to resolve old traumas and come out the other end with a new sense of hope, while others succumb to their inner turmoil and fade away. Some find a troubling, uncomfortable sense of victory, and others experience a glorious, defiant defeat. I can’t understate how revolutionary the series was back when it came out. Its serious, mature storytelling elevated superheroes from cheap, pulpy cartoons to sophisticated, tragic literary creations. Watchmen was the “moment when comics grew up” and the industry realized that it could tell grander, darker, sharper, more adult stories.

Watchmen‘s superhero story doubles as a commentary on the nature of superhero comics, a pointed and insightful meditation on why we read them and why we like these characters. If Moore’s analysis of his own profession can feel grim and savage, it’s because he saw the dark heart beating beneath comics. Moore uses Watchmen to take stock of the comic industry and its readers, pointing out what we had all been missing about superhero stories. Gibbons’ art, like Moore’s writing, is similarly dark, sober, and intensely detailed.

Because Moore and Gibbons want to tell a story about comic books, they utilize every trick in the comic book arsenal to tell that story. They are especially interested in how we are usually asked to read comics and how we typically move from panel to panel on a comic book page.

For instance, the panel layout in Watchmen‘s fifth issue is symmetrical – the form, shape, and composition of how each panel is arranged on the first page of the issue matches the form, shape, and composition of how each panel is arranged on the last page of the issue. This mirroring continues throughout all of the issue’s pages, like a series of reflections, with the layout on the second page matching the layout on the second-to-last-page, and so on.

The symmetry culminates in the middle of the issue, in a central panel featuring hero Adrian Veidt striking down an attacker, both their bodies arranged in an X-shaped composition that splits the issue in half. This formal play isn’t meant to be a secret: Moore and Gibbons want us to know what they are doing. The symmetrical issue is titled “Fearful Symmetry”, after all.

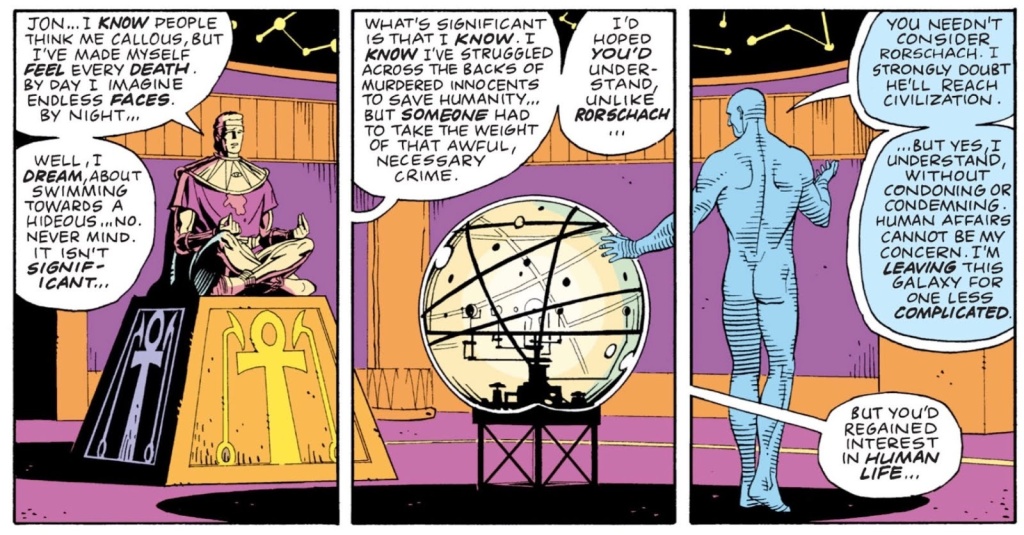

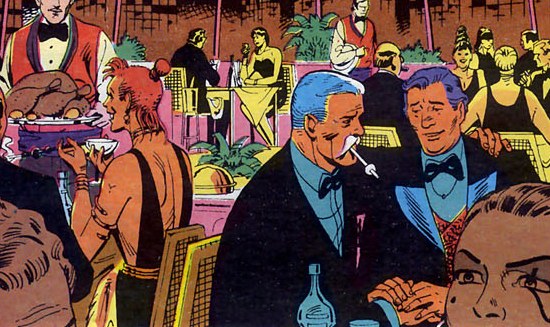

Watchmen also plays formal tricks with its panels in examples like the above spread, in which we get a panoramic triptych of two characters talking. In a film, this shot might be rendered as a pan from left to right; or maybe we’d get two or three shots that focus on each speaker, one at a time, with a single wide shot of the characters facing each other to establish where they are in relation to one another.

But in this comic spread, we’re able to get all these options at the same time: the panels are composed as a pan (imagine your eye as the camera as it moves across the page), as a series of three separate shots, and as a single wide shot where we see everything at once.

It’s a subtle but virtuoso moment, and it’s the sort of formal flourish that you can only pull off by using a comic book’s unique brand of sequential narrative art.

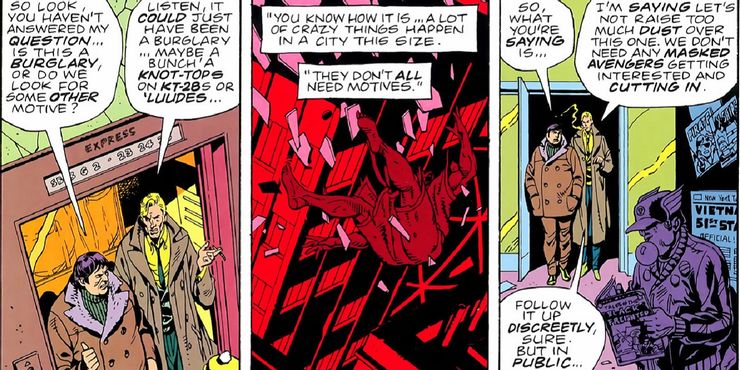

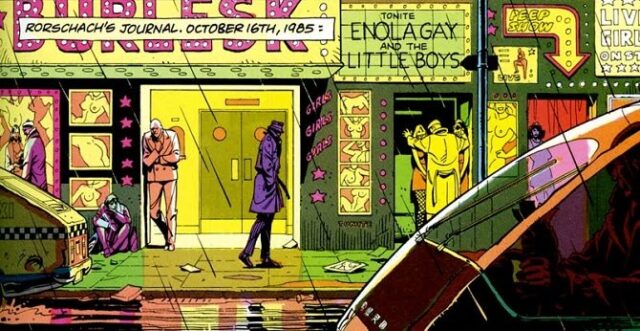

Watchmen‘s panels are also peppered with hidden images, little asides that we’re expected to gloss over and then notice on a second reading, or that we might only catch out of the corner of our eye as we move from panel to panel and page to page.

For instance, Watchmen tucks away major world-building elements in its margins, like the fact that, in its version of the Vietnam conflict, Vietnam was conquered by the US and annexed as the 51st state (see the newspaper near the bottom right of the third panel above).

Other panels are crammed with blink-and-you’ll-miss-it surprises. In the panel above, a fancy restaurant overlooks the city. On the left, a table is served their order: a whole chicken with four legs. It looks like the mid-twentieth century’s nuclear paranoia has resulted in a world where radioactive mutation is commonplace and socially accepted.

Meanwhile, in the foreground, two older gay men hold hands and look at each other fondly. It’s a simple but bold statement about how Watchmen‘s world feels about sexuality, and a pointed declaration by Moore, writing as he was in the conservative Thatcherite England of the 1980s: Watchmen may be filled with violence and insane superheroes, sure, but at least its alternate universe society is well-adjusted enough to accept homosexuality (to a certain extent…see the comic’s subtle, tragic side story about the old hero Hooded Justice).

What makes this panel something that only a comic book can pull off? Well, let’s try to see if we can adapt the panel into prose. Our hypothetical Watchmen novel might read something like this: “the waiter served a steaming four-legged bird to a group of grateful patrons, while two men held hands nearby, decked out in evening wear.”

We adapted the content of the panel, but we couldn’t adapt its formal value. We had to make its imagery explicit and obvious, while the comic’s creators placed the panel’s details in a way that doesn’t ask for direct attention. It seems clear that Watchmen‘s readers aren’t expected to notice these details right away; they are intended to be noticed obliquely out of the corner of the reader’s eye, maybe during a second or even third reading. It’s possible that a number of Watchmen‘s readers will go through the comic several times without ever registering what we’ve discussed here.

But that’s okay. It’s part of the formal game here, proving that story details can be hidden in a comic book panel in a way that a novel or a poem can’t replicate. Even a movie couldn’t do the same; we don’t watch films one frame at a time in the same way that we read comics one panel at a time, so while something might be hidden at the edges of a film shot composition, it’ll blow by us and we need to watch the entire film again to see it (assuming that the movie was meant to be seen in a theatrical setting, which may become more rare in coming years). In a comic, we always have all of the information we need in front of us at any given time, so we can flip back and forth from page to page on a whim or to catch something that we think we saw a little earlier.

How would a movie adaptation even begin to deal with the comic’s formal specificity?

Watching Watchmen

Somebody actually made a Watchmen movie: Zack Snyder, best known these days for an ill-fated attempt to create a DC Comics cinematic universe, directed a Watchmen back in 2009.

I’ll start off by saying that Snyder’s movie does have its merits – the cast is really pretty good, especially former child actor Jackie Earle Haley as Rorschach – but it ultimately fails to capture the main purpose of the original comic on multiple levels.

Let’s take one of the comic panels that we talked about earlier, with the four-legged chicken. In the Watchmen movie’s equivalent dinner scene, we overhear an extra say “I’m so glad that I ordered the four-legged chicken.” It’s not quite the same, huh? Firstly, it makes the comic’s joke about the mundanely radioactive alternate future obvious, which takes away a lot of its satirical bite. There’s no grace or wit or subtlety, so the implication becomes too blunt. Next, it betrays Moore’s intent to keep this sort of thing hidden, something glimpsed at the side of the panel and only noticed with surprise. The formal flourish is lost. In the movie, we have to hear the extra’s dialogue, but it’s easy to miss the chicken’s four legs in the comic.

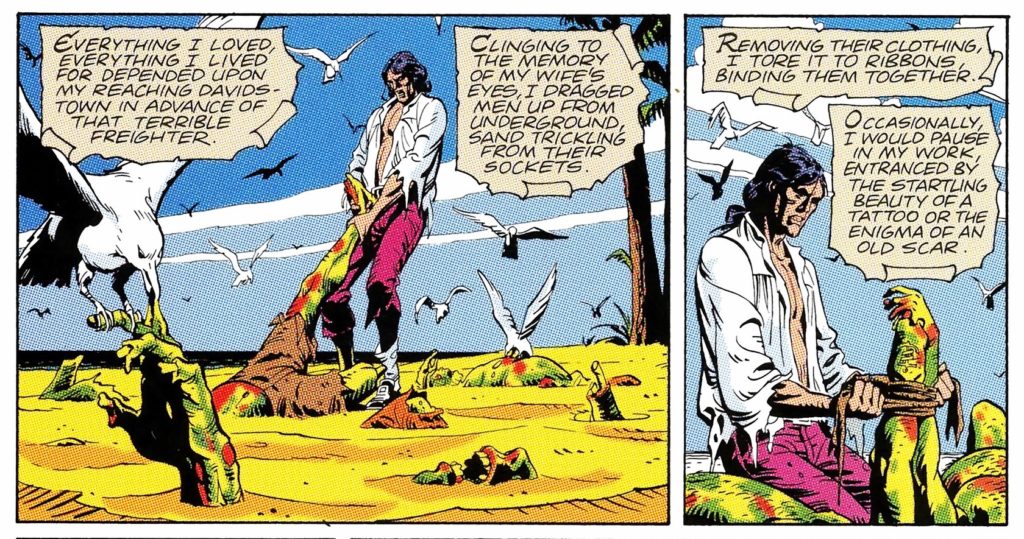

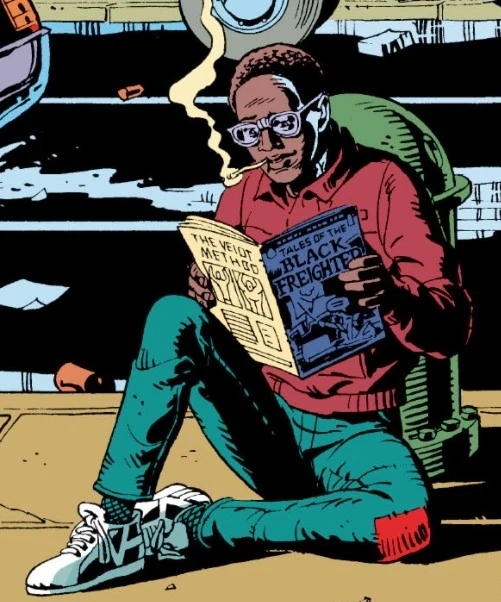

The Watchmen movie is forced to constantly cut corners and excise essential formal context like this. For instance, the original comic is punctuated by references to and excerpts from a comic book called Tales of the Black Freighter. It’s a comic that Moore and Gibbons invented for the Watchmen universe, giving it an elaborate publication history and crediting real comic book artist Joe Orlando as part of its art team. Black Freighter is a pirate horror comic; Moore reasoned that an alternate history world where superheroes really existed might not be too interested in superhero comic books and that the medium would seek out other subjects for stories of mystery and adventure.

Several characters in Watchmen read Black Freighter, particularly a young guy named Bernie who hangs out at his local newsstand. We peek over Bernie’s shoulder as he reads the comic. It becomes clear that the events of Black Freighter are a kind of cryptic commentary on what happens in the larger Watchmen story. The hero of Black Freighter faces tough and horrible choices, just like some of the characters in Watchmen; his grim, dark tale of survival also has many parallels with the earth-shattering events at the end of the Watchmen story.

Snyder’s movie doesn’t attempt to include Tales of the Black Freighter. Snyder knew that it was important to adapt for some reason, so he produced an animated episode based it, releasing it as a separate DVD. This defeats the entire point, of course – if Black Freighter isn’t interlaced into the format of Watchmen itself, it doesn’t have any meaning. It’s been divorced from the context that gave it purpose. If it’s not directly commenting on the Watchmen story, it doesn’t have anything to say, except to be a decent pirate adventure. It would be like releasing a set of notes and annotations for a poem without including the text of the poem itself.

There’s also the fact that the intended metatextual value of Black Freighter is that it’s a comic inside of a comic; Moore uses a comic book to comment on his comic book, because he feels that only a comic can understand itself. In the case of Snyder’s adaptation, however, we get a direct-to-DVD animated short made available two weeks after the release of Snyder’s movie. The spiritual link between Watchmen and Black Freighter in the original comic book no longer makes sense here. This is then on top of the fact that, because of the way that the Watchmen movie and the Black Freighter cartoon were released, the overwhelming majority of viewers who went to see the film never saw the cartoon and probably didn’t realize that it existed.

Snyder simply had no idea how to make Black Freighter work in his movie. Other extra details and unique interludes from the comic, like the way Moore includes excerpts from Under the Hood, an illuminating memoir by retired superhero Hollis Mason, likewise end up either cut or relegated to the DVD special features section.

You might counter my critique by saying that though Snyder’s film doesn’t (or can’t) adapt all of the metatextual and in-universe material that Moore created for Watchmen, it manages to properly adapt the actual story, which, one would think, is more important.

But even if we are willing to leave aside the fact that these metatextual interludes are vital to Watchmen‘s meaning, the movie still doesn’t get things right. Yes, it successfully stages many scenes from the original comic, but it consistently fails to understand their tone or emotional texture.

This is especially evident in the film’s soundtrack, like the use of Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Sound of Silence” during a funeral scene; the poetic 1964 song was already outdated within a few years of its recording and it would have been considered very hoary in Watchmen‘s 1980s era. It makes Watchmen feel clunky and out of step instead of edgy and revolutionary, which is how it felt when it was first released. Even worse is a bad sex scene set to Leonard Cohen’s cover of “Hallelujah”, the editing of which is too preposterous to believe.

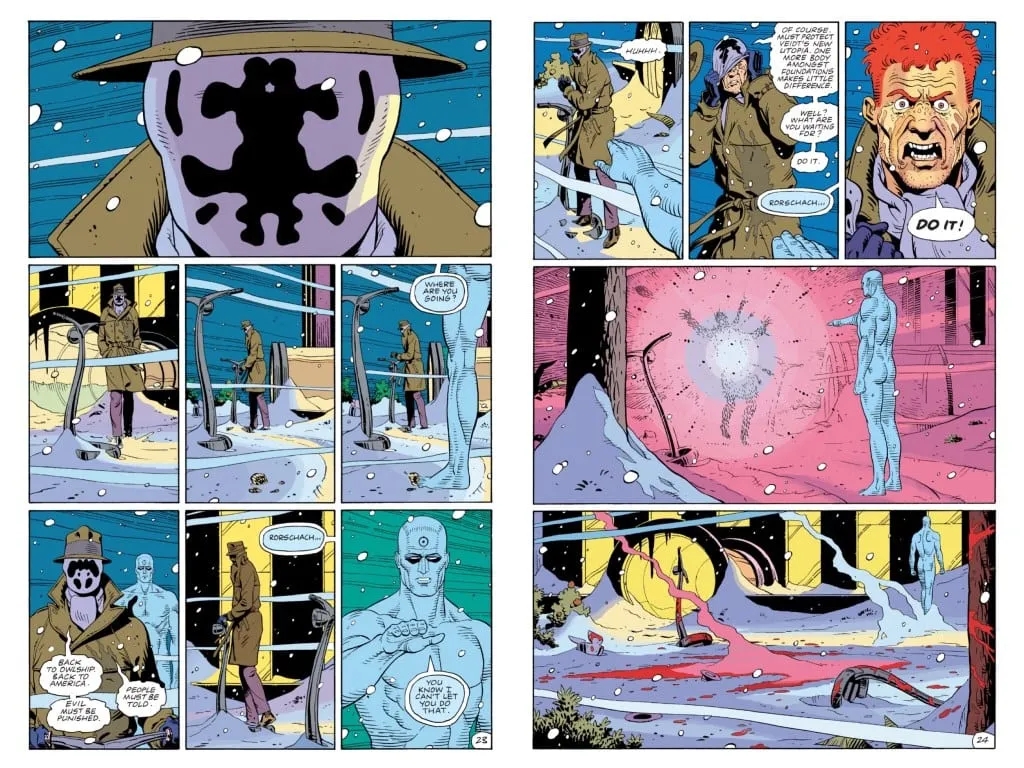

The movie also adds other obtrusive, cheesy elements that undercut the emotional interests of the comic, bringing no new value or insight except for the most formulaic cinematic tricks. For instance, when the increasingly inhuman character Dr. Manhattan kills off the grim anti-hero Rorschach at the end of the comic, the scene feels lonely and inevitable. Dr. Manhattan can’t allow Rorschach to leave their remote arctic location alive, because the latter insists on revealing the truth behind a terrible plan to achieve world peace (the plan requires the death of millions, and Rorschach refuses to sign off on it). Rorschach knows that Manhattan will kill him, but his values won’t allow him to compromise. Rorschach demands that Manhattan “do it!” and Manhattan complies, vaporizing him. All that’s left is a pink smear and a bit of steam.

The staging of the scene emphasizes Rorschach’s resolve and Manhattan’s icy composure as he executes his one-time ally. The sequence is intimate and presented with minimum affect, aside from a brief moment of tearful anger from Rorschach. We aren’t asked to feel good or bad about what has just happened, and we aren’t expected to be sad for Rorschach or mad at Manhattan. What happens is offered as simple fact. The neutral emotional landscape that we see in these two pages, free from theatricality or sentimentality, is a great example of the Watchmen comic’s unique tone. Moore and Gibbons could give us big, bold, and ostentatious comic book pathos here, but they choose not to do so. They decided it’d be more interesting to pull back.

Snyder’s film, however, makes this into the same climax we’ve seen many times before, with an emotional outburst straight out of Star Wars. In the movie, Rorschach’s friend, the middle-aged superhero Nite Owl, is standing by and watching the whole scene play out. Rorschach is vaporized, and Nite Owl delivers a cliche “Nooooo!”, falling to his knees in despair. Nite Owl’s hands go to his mask, ripping it off so we can see all of actor Patrick Wilson’s performance. In the next shot, we crane above a bloody snow angel composed of Rorschach’s remains, as his trademark hat flutters dramatically in the arctic breeze and comes to a rest on the earth. It’s a clumsy and overt scene where the original is sober and understated. The imagery is there, but the tonal purpose wasn’t carried over.

And this is before even getting into how the movie constantly accentuates the comic’s scenes of violence, sexing them up so they seem neat or dramatic instead of disturbing. This has the unfortunate byproduct of making some of the comic’s most psychotic characters seem more attractive or sympathetic than they were ever intended to be. Watchmen‘s The Comedian, for example, is a deranged rapist in the comic book, but the movie reimagines him as something closer to a troubled but cool and hard-boiled man of the world.

The comic has a flashback scene in which The Comedian kills a Vietnamese woman (pregnant with his child) after she cuts his face. He is humiliated and enraged by this injury, exposed as vulnerable, and he lashes out at her in a brutal tantrum, mocking and insulting her before he kills her. We see a desperate and ugly attempt to recover his wounded masculinity; he’s just a toxic, savage loser. The film version of this scene finds a very different Comedian. Here he is aloof and frosty; after the woman slices him, he shouts “My face!” – not sounding remotely humiliated or violated, just pissed and still in control – then stoically reaches for his weapon, turns it on her, and fires. He appears unperturbed and not desperate or ugly. He’s cool as a cucumber, removed from it all. It’s a total misread of the character.

[Though, to be somewhat fair to the movie, the recent Before Watchmen prequel comic book (not written by Moore), makes the same error in judgment, now portraying The Comedian as a real dude beneath it all, maybe he’s raped or killed a few folks, but at heart he’s a “macho antihero…a man whose heroism lies in his manly indifference as to whether the world sees him as a hero.”]

But really, whatever we can say about what the film cuts out or its tacky artistic decisions, it’s all about one central problem: adapting Watchmen into a film is like adapting a glass of water into a film.

Wait, what?

Adapting Water

Imagine a glass of water. When you pour out a glass of water, you want to drink it. That’s the point of a glass of water, right?

What if you adapted a glass of water into a movie? It might look great – tall, frosty, and simply glistening with refreshment – but you can’t actually reach into the screen and drink it. This so-called adaptation has stripped the glass of water of all of its utility and purpose.

Some fans and pundits have chalked up the Watchmen movie’s faults to the fact that it is just too beloved or outlandish to faithfully adapt, as in this post from Syfy Wire:

But forget how difficult it would be to make a movie adaptation that makes the fans happy. How do you deal with the actual logistics of the thing? You have to have the characters age decades. You have to introduce absurd concepts that were designed by Moore specifically to work only on the page. And what about Dr. Manhattan’s nudity? And what about the squid?

But the Watchmen film’s problems have nothing to do with the fact that Dr. Manhattan walks around naked (he is a quantum being who transcended worldly interests, after all) or that an alien squid shows up at the end of the comic’s story (it all makes sense, I promise). I also feel that fans of a given comic book or novel can be really quite forgiving if the filmmakers behind an adaptation try really hard to get it right. No, none of this is really the problem here.

The issue is that a Watchmen film will never, by definition, share the original’s formal context, and so it can never accurately reflect its intended story and meaning, which are, at the risk of repeating myself, about that formal context. Watchmen is a comic about comics, written to be read as a comic, drawn to be seen as a comic. The formal context is essential.

Even when multimedia engagement with Watchmen is good and competently executed it still feels hollow, because it lacks the original’s formal purpose. HBO’s Watchmen mini-series isn’t an adaptation of the comic – it’s a semi-sequel and a remix – and it’s actually interesting and beautifully produced, but it falls into many of the same traps as the film. It’s a TV series. The original Watchmen is a comic book. The original Watchmen has nothing important to say about TV shows. It cares about comics. As great as HBO’s Watchmen might be, all of its plots and history and characters are based on a comic. It’s a TV show about comics about comics. That doesn’t make sense.

What was the point that Moore and Gibbons wanted to make by being so formally specific in Watchmen? Was it all artistic bravura in the service of their chosen art form: look what comics can do, folks? Is it about experimenting, pushing comics to the limit, testing them, exploring how our relationship with them might be playfully expanded and carefully manipulated?

I think all of these elements are at play, but more than anything, Moore and Gibbons seem to say that if Watchmen is about comic books, its formal dimensions need to reflect that interest in comic books. Marshall McLuhan said that the “the medium is the message”, which means the way content is delivered is just as important, or more important, than the content itself. I see Watchmen as a potent exercise in McLuhan’s statement: the “story” of Watchmen isn’t just the story in the panels, involving the fates of these superheroes, but the actual act of reading the book and discovering, bouncing off, recognizing, and engaging with its formal features.

I wrote this article because we need to think about the ways that projects are bound to their original medium when we make an adaptation. The Ringer declared that there are no more “unfilmable” books and that anything can be adapted, citing successful adaptations of Dune, Foundation, and The Wheel of Time, all three of which were once thought, indeed, unfilmable. But the idea of “unfilmable” is about more than just being really long or requiring a bunch of special effects. What about the projects that are glasses of water – the projects that will lose their basic purpose and meaning if we divorce them from their formal context?

If the Hyperion movie actually gets made, will it make much thematic sense to see Keats on the big screen? As I stated before, the whole point of Hyperion‘s use of Keats is that the poet comes back to life in a book, on the page, resurrected in a novel. If L’Incal actually gets made into a movie, how will the filmmakers translate its most essential feature: the scale, rhythm, and specific style of Moebius’ graphic art? I’m highly skeptical about the idea of Moebius’ art being rendered in gaudy CGI.

I understand that most of this stuff gets made for financial reasons, but taking the problem from a purely creative angle, we don’t need to adapt everything. Watchmen was made in an exceptionally specific way in a specific medium, and trying to transplant it will leave it dead.

If you’ve got a glass of water in front of you, just drink the damn thing.

Film something else.

Notes

- I think it probably goes without saying, but to be clear, I’m not opposed to adaptation as a rule – there are plenty of great adaptations, and they can be awesome! My argument is entirely about particular works of art that resist adaptation because of how specifically indebted they are to their medium.

- The Watchmen mini-series on HBO tried to mimic some of the original comic’s clever and thematically relevant use of supplemental material, but, of course, it was impossible to include things like diary entries and newspaper clippings in a TV show. This material was published on an online archive called “Peteypedia” (named after a police officer character who tries to become a superhero in his own right). This was an admirable attempt make something cool, but it doesn’t really do the same work as the Watchmen comic did. In the comic, this supplemental material was interlaced into story’s formal structure, so all of it is interconnected. The idea of switching between a TV show and a promotional site to get the complete picture doesn’t really have the same ring to it, does it?